The response of some Richmond area law enforcement officials to the COVID-19 pandemic is more than disappointing. It is life threatening. Virginia’s dedicated law enforcement, correctional officers and other staff protecting our communities and working in custodial facilities, such as prisons, jails and detention centers, deserve the utmost protection from exposure to the virus, as do the people housed in them. The reduced intake of people into custodial facilities is necessary for their safety and the safety of staff. Close coordination and alignment between and among the many various law enforcement, judicial and correctional agencies in our area is essential to ensure an effective system-wide response in custodial facilities that controls the spread of the virus, which includes choosing not to take into custody and to release from custody anyone who is not a danger to the public.

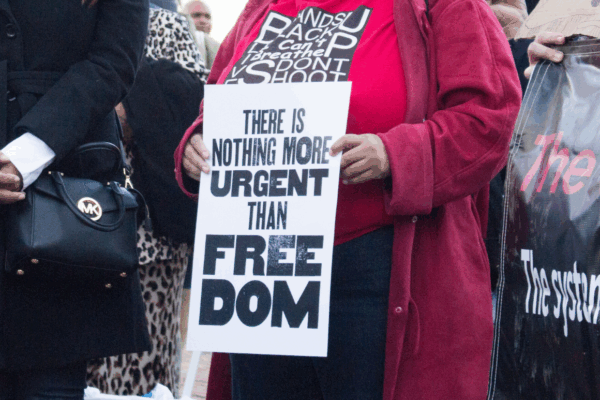

No one is asking law enforcement to release or fail to arrest anyone whose presence in the community represents a direct and imminent threat of harm to anyone. We are asking our community leaders and law enforcement to recognize, however, that now is the time to rethink how our jails and prisons are not effective ways to address the social and community ills of poverty and drug use, and to recognize that we have defined certain behaviors as needing a “criminal’ law enforcement response that are the result of poverty or addiction rather than offer treatment in a public health setting.

We are asking our community leaders and law enforcement to recognize, however, that now is the time to rethink how our jails and prisons are not effective ways to address the social and community ills of poverty and drug use, and to recognize that we have defined certain behaviors as needing a “criminal’ law enforcement response that are the result of poverty or addiction rather than offer treatment in a public health setting.

Our legislature long ago set policy for law enforcement to follow that states that, except in very limited circumstances, police “shall” issue a summons to and release anyone who commits a misdemeanor in their presence rather than take them into custody and admit them to a jail. We are asking that law enforcement implement this law as written unless the person committing the misdemeanor represents a direct and imminent threat of harm. Taking this step will have a direct and positive impact on the populations of our local and regional jails, too many of which are overcrowded, allowing implementation of COVID-19 safety precautions to protect the people and staff who remain there.

It is also a good time to ask ourselves why any person who is not charged with or convicted of a criminal offense should be held in a jail or prison, and to release from our institutions anyone who is being held on a civil detainer, including immigration detainers.

Finally, we must ask ourselves why it is that people who are not convicted of anything and are presumed innocent are being held in jail pending their trials, not because they are dangerous to anyone, but because they cannot meet artificially imposed conditions of release including payment of bail.

To hear law enforcement officials talk about their work as if it is a business that needs a bailout in a time of economic uncertainty or in a way that hypes unreasoned fears of the public is disheartening. This is particularly true in a circumstance in which these same individuals continue to over-police communities of color and arrest Black people more frequently than white people for the same crime. It is time to jettison the “tough on crime” hyperbole and recognize this pandemic as an opportunity to rethink the way we choose to use the criminal legal system to address issues of poverty, income inequality and addiction.