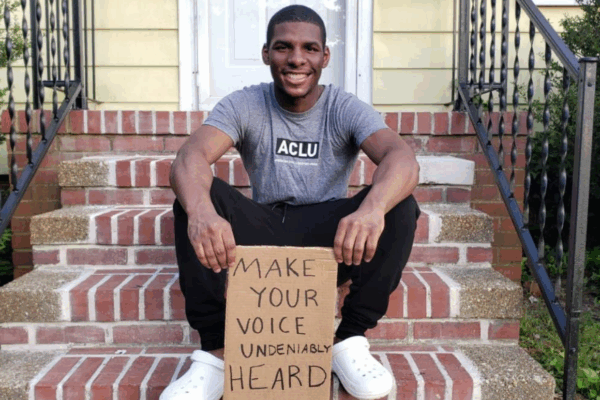

These are my thoughts and my thoughts only. The ACLU of Virginia has only provided me the opportunity to portray those thoughts onto a larger platform.

Most of my life, I’ve been the guy in a suit. Make no mistake, I’ve grown to love the feeling a custom garment gives me – influence, dignity, respect. However, as I’ve grown older, I’ve begun to understand that the stylish piece of clothing I wear is only a sad response to something that has been deeply entrenched in the confines of America’s systems: implicit bias. As a 19-year-old Black man navigating a world enmeshed with implicit bias, I’ve always heard and seen things differently depending upon which article of clothing I wear, be it a hoodie or a suit.

While in a hoodie, I notice sly looks and clutched purses that make me feel secluded, even though I may be around hundreds of people. While in a hoodie, I recognize the racial back tones to the most mundane tasks from driving to walking on the sidewalk to waiting on my father to return home from work. The power of the hoodie nuances my insight of the world when I’m driving, as I recognize the tension circulating through my body when the red and blue lights are flashing behind me. In this situation, the hoodie causes me to understand that I must be perfect. If not, that broken taillight, that missed signal, that miscommunication, that failure to remain silent, that simple encounter with an officer may result in embalming fumes and my casket. My ability to recognize the implicit forms of the stereotype of a young Black man is similarly activated while simply walking through my PWI (predominantly white institution) in a hoodie. Noticing the subtle moments when people cross the street to avoid an uncomfortable encounter, the sideways looks in the classroom, and being presumed guilty based upon prejudice about the melanin in my skin are all epiphanies I have when I’m clothed in a hoodie.

As a 19-year-old Black man navigating a world enmeshed with implicit bias, I’ve always heard and seen things differently depending upon which article of clothing I wear-be it a hoodie or a suit.

To amplify the significance of the hoodie, I often ponder over moments when my family awaits the return of my father from work. My father, a current U.S. postal worker and former Virginia sheriff officer, often works long-daunting hours supporting the efforts of a country that once enslaved his ancestors. During his long hours of flowering through various mail packages, my mother, sister and I anxiously await his return. Our anxiousness derives from our uncertainty of his return. Our anxiousness derives from the countless images we see on news platforms of Black men slaughtered by police officers – people who are meant to protect us. Similarly, our anxiousness derives from the understanding that he could be murdered by one of his own people that has fell subject to yet another phenomenon within the Black community called “crab in a barrel mentality”. Ultimately, our anxiousness derives from the coherent understanding that despite being a former officer, society couldn’t care less about his title – only the color of his skin and what services he can provide for their financial gain. All of these cruel, yet truthful realizations derive from the power of the hoodie.

Although the hoodie provides me one lens of the world, in the same vein, a suit changes my views of its dynamics. In a suit, I have respect. In a suit, I have influence. In a suit, I feel like I finally belong as a young Black man in a white man’s world. Similarly, the world views me in a different light – as a spectacle. The smiles, handshakes and countless opportunities I have received from people, particularly older white men, have happened as I was dressed in a custom-tailored suit and tie. In a hoodie, these opportunities would be nonexistent.

People, especially those in positions of power, fetishize over an intelligent, articulate, ambitious Black man, but only when that Black man looks “presentable” in a suit and “knows his place” in the world. As long as I “stay in line” or replace my native language of Ebonics with Standard American English, people claim “the sky is the limit” for me. In other words, as long as I shade my Blackness, I’ll be successful.

Although I utterly cherish the altered perspective that the suit gives me, it also hurts. It pains me. It pains me because despite my altruistic personality, despite my profound dedication to scholarship, despite being a genuine person, I’m still judged by a preconceived notion of my Blackness. It pains me because it honestly makes me feel small in comparison to the world. The world is so vast and grand with many variables affecting one another. It pains me because it often causes me to ask the question, “Am I willing to give my life to serve the greater good of a population without certainty that I’ll ever truly make that change?”

This is why I’m angry. This is why I’m often confused. This is why I protest. This is why I read. This is why I analyze. This is why I think. This is why I march with my fists held up. I amplify my voice because I understand that in the face of my successes, my Blackness can potentially prevent me from gaining more of that success. I’m still misunderstood. I’m still judged. I’m still ostracized. I’m still jailed. I’m still misrepresented. And in this case, it’s almost likely as possible for me to be murdered by people who carry the badge as it is to be murdered by people who look exactly like me. Although the healing and process of racial reconciliation has begun in our country, I ultimately understand that the fight and struggle will never be over, simply because of the hate, and confusion, of the melanin and Blackness engrained in my blood. Those are the gifts, and curses, that a simple garment can cause – all by wearing a suit or a hoodie.